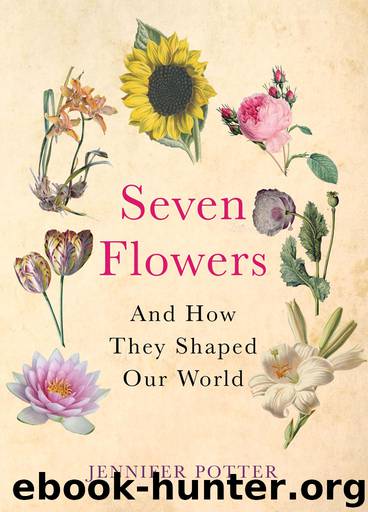

Seven Flowers by Jennifer Potter

Author:Jennifer Potter [Potter, Jennifer]

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781782390374

Publisher: Atlantic Books

One of the Roman’s fiercest critics was the lyric poet Christine de Pizan, who turned to poetry some time after the death in 1390 of her husband, a secretary to King Charles VI of France. Accusations and counter-accusations flew back and forth about the effrontery of seeking biblical support for sanctifying a woman’s ‘little rosebud’. Were the poem’s defenders led astray by St Luke, thundered one of de Pizan’s supporters, when he declared, ‘Every male that opened the womb shall be called holy to the Lord’? Using poetry to advance her cause, de Pizan composed her riposte Dit de la Rose in 1402, in which she was asked, also in a dream, to found a chivalric order that would bestow its ‘dear and lovely roses’ only on those knights who upheld a woman’s virtue and reputation, in obvious contrast to Jean de Meun, who viewed a woman’s ‘rose’ as there for the taking. (Britain’s Knights of the Garter follow in the tradition of decorating their collars with roses.)

De Pizan situated her narrative on St Valentine’s Day, commemorated to this day as the occasion for lovers to exchange tokens of their affection – traditionally red roses – but then only recently ‘invented’ as a day for lovers, apparently by the English poet Geoffrey Chaucer and his circle. In his poem the Parliament of Fowls, Chaucer chose the feast day of the martyred St Valentine, 14 February, to mark the annual gathering of birds for the purpose of choosing their mates, although no one is quite sure why this particular saint should be linked to the first matings of spring, when the weather is hardly springlike.

In an irony worth savouring, it was Christine de Pizan, the arch-critic of the Roman de la Rose, who added roses to the celebration. She would have hated the ribaldry and innuendo with which many later writers treated the rose – most of all, Shakespeare, for whom the ‘bud’ of a girl’s adolescence was ripe for the plucking but immediately lost its freshness as the flower opened and became (over)‘blown’. Shakespeare was drawing on a rich seam of Elizabethan slang in which the rose took many meanings, pre-eminently sexual ones, as maidenhead, vulva, whore, courtesan, young girl, sexually used woman, syphilitic sore; to ‘pluck a rose’ might imply either taking a girl’s virginity or pissing in the open air. Yet Shakespeare could equally use the rose to express the tragedy of time passing and a woman’s fading beauty, as in Cleopatra’s anguished cry:

See, my women,

Against the blown rose may they stop their nose

That kneeled unto the buds.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4796)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(4457)

All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot(4303)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3949)

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid(3819)

Origin Story: A Big History of Everything by David Christian(3679)

COSMOS by Carl Sagan(3616)

How to Read Water: Clues and Patterns from Puddles to the Sea (Natural Navigation) by Tristan Gooley(3454)

Hedgerow by John Wright(3348)

How to Read Nature by Tristan Gooley(3322)

The Inner Life of Animals by Peter Wohlleben(3302)

How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell(3291)

Project Animal Farm: An Accidental Journey into the Secret World of Farming and the Truth About Our Food by Sonia Faruqi(3211)

Origin Story by David Christian(3191)

Water by Ian Miller(3174)

A Forest Journey by John Perlin(3062)

The Plant Messiah by Carlos Magdalena(2919)

A Wilder Time by William E. Glassley(2854)

Forests: A Very Short Introduction by Jaboury Ghazoul(2831)